‘Performance begins where memory leaves off.’

Any high-performance athlete or coach will tell you this, and it applies equally well to the performing arts.

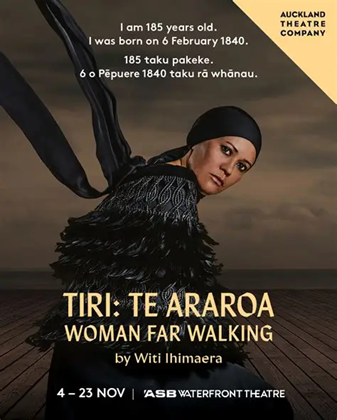

I thought about this quite a lot last evening as I blubbed my way through Auckland Theatre Company’s watershed production of Tiri: Te Araroa Woman Far Walking, directed by Katie Wolfe (Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Tama) and written by Aotearoa’s crown prince of storytellers Witi Ihimaera (Te Whānau a Kai and Ngāti Porou). Yes, it’s a tearjerker, but not in a soap opera-ish way, more in line with having your most intimate emotional ‘withers wrung’ through anger, laughter, rage, incredulity, fury and every emotional bus stop in between.

Add an absolutely magnificent assurance in the delivery of complex, often dense, material all enveloped in a cloak of visual and aural spectacle, and you’ll be getting close to what I experienced.

So, tears.

Not just me, but the elderly pakeha woman next to me as well who illustrated her joy by elbowing me in the ribs and snorting every time she saw something that tickled her Remuera fancy.

A form of collegial colonial bonding like I’d never experienced before.

Stripped back, it’s just a couple of actors in literally an empty space, and a whole bunch of people behind the scenes supporting the performers in a well-resourced and comfortable theatre.

There’s nothing new about that, it just happens that this is different, this isn’t your everyday, this is truly outstanding work, as good as you’ll see anywhere, at any time, and it’s political, so let’s move on.

I’m very fond of the ASB Waterfront Theatre, not because of all the above – that too, of course – but because it’s a calm, quietly welcoming, and emotionally neutral space, perfect for this reasonably socialized, elderly introvert who must sit alone for 20 minutes while the Plus One parks the car and walks back to the theatre. Picking up the tickets from the box office is always a pleasant experience here, even when I forget to tell the boxie what my name is. She handles that sort of nonsense much better than I do.

Now I can sit in the beautifully appointed foyer on comfortable seating without having to worry about being hassled by energetic staff trying to sell me stuff. I’m not good at dealing with that type of corporate pestering and thank the Lorde, ATC staff don’t ever do that, they’re kind, polite, sensitive, and always helpful.

There’s a classy A5 programme, nuanced, tasteful, informative, easily accessible, and free.

I like that too,

All this achieved, Plus One arrives and we decide on food, I choose a pizza with mushrooms and a wide range of vegetation along with a coffee, she has kumara chips and a gingerella. The options are wide-ranging and the prices reasonable. The food arrives and it’s seriously good. The foyer fills up, and the chatter is not at all invasive. No hoons here. We chat with a couple of elderly pakeha ladies with whom we share a couch and who seem to be representative of this particular audience – mostly subscribers, pakeha, conservative, comfortably off, traditional theatre goers of the blue rinse brigade.

Some things don’t change.

That’s oddly comforting, but I have some idea of what’s to come, and maybe they don’t.

I wonder as we enter the auditorium whether this audience is quite prepared for what they are about to receive. We’ll know the answer to that in around 100 minutes.

John Verryt’s magical set design consists of a wide, white, speckled pathway, a rostrum, diminishing as it rises to a back-lit starry doorway upstage, the cosmos in one bite. We watch as it evolves before our eyes, at once a road, now a river of blood, back to being the cosmos, blood again, while the doorway becomes a pictorial frame for the lighting genius of Jane Hakaraia (Ngāti Raukawa) – explosions illustrate the Goblin Wars, there’s a crucifix, and we see Tiri’s moko kauae, the right of all wāhine Māori and a taonga gifted to her by her tupuna, take shape. Sheer technological brilliance. I remember reading how Professor Leonie Pihama was visited by her mentor who told her that it was time. ‘Time for what?’ Pihama asked, only to be told ‘it will be in the summer.’

And so it was.

Years ago now.

Lights down, and ‘it is time’, time, in the words of Kaihāpai Reo Māori and Translator Maioha Ki Te Ao Tūroa Allen (Ngāti Apakura, Waikato Maniapoto), time for us to ‘walk, even for a moment, along the path of remembrance, resilience, return, and reclamation’ with this outstanding team.

Remembrance starts for me on 20 June 2000 when Taki Rua Productions brought the first iteration of Woman Far Walking to Tāmaki Makaurau and set it down in the Herald Theatre. Rachel House played Tiri (short for Te Tiriti o Waitangi Mahana), Rima Te Wiata was her antagonist Tilly, and Cathy Downes directed. New Zealand Herald reviewer Susan Budd and I saw the show on opening night, and Budd reflects that ‘Tiri Mahana is named for the tiriti that she describes bitterly as a fraud. In a powerful opening speech, she relates the coming of the Pakeha, “hairy goblins,” and laments her status as a freak and aberration who has outlived all she loves. She rails and wails, comedy and tragedy alternating in a fantastic aria.’

Generous words from the respected Herald reviewer.

Founded in 1983, Taki Rua has always been an arts industry leader, a creative rule breaker, continually evolving, seeing theatre through a distinctively Māori lens, and challenging the definition. Thanks to Taki Rua, Māori voices have been heard worldwide, and they’ve stuck to their weaving for decades, rain or shine.

The premiere had been at Soundings Theatre in Pōneke on 17 March 2000 and the following year the show touring nationally still with House but with Nicola Kawana playing Tilly. In 2002 the Taki Rua production toured internationally with Riria Hotere as Tiri, Kahu Koroheke Hotere as Tilly, and directed this time by the late Nancy Brunning. These memories are special for my Plus One because Kahu Hotere had been her teacher and the Hotere girls her childhood playmates.

So, why talk about this? It’s just history and a history that’s not likely ever to find its way into an Aotearoa history book or performing arts curriculum assuming we still have these luxuries when the current regime completes its cultural whitewash.

For me, it’s because, when asking the question ‘how did we get to this point’, we can perhaps catch a glimpse of where we go next, and because it’s a journey that walks hand in hand with Tiri’s.

And it’s ours.

Ma whero ma pango ka oti ai te mahi.

When my professional theatre career began in 1975, Aotearoa New Zealand had six career-affirming theatres and none, prior to 1980, had any real record of staging Māori theatre, with Downstage being somewhat of an outlier.

The Golden Lover (1967) was a landmark event for Māori theatre. Written by Douglas Stewart and directed by Richard Campion for Downstage, it featured a cast with many future stars of Māori theatre, including Wi Kuki Kaa, Don Selwyn, and Harata Solomon.

Bruce Mason’s Māori Plays, while written by a Pākehā playwright, were a significant part of the New Zealand theatrical landscape, and some were staged at Downstage. His best-known work, The Pohutukawa Tree (1956), explores the complexities of Māori-Pākehā relations as does Tiri: Te Araroa Woman Far Walking, but there the similarity ends.

Harry Dansey’s Te Raukura: The Feathers of the Albatross (1972) was one of the first plays by a Māori writer to be professionally performed and published in Aotearoa. It dramatised the passive resistance movement of Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi at Parihaka.

A rebirth of sorts.

Hone Tūwhare’s In the Wilderness without a Hat (1975) and Rore Hapipi’s Death of the Land (1977) followed, with the latter being toured by the contemporary Māori performance company Te Ika a Maui Players in 1976.

The Mercury, Theatre Corporate, Centrepoint, the Court, and the Fortune made not a ripple on the waters of biculturalism, and the funding bodies did little to help either.

Downstage was certainly a flickering light in the monocultural darkness, but things slowly began to change and it was dedicated Māori theatre groups, often using collective creation methods and focusing specifically on Māori land rights (Takaparawhau / Bastion Point, Raglan Golf Course), on Kōhanga Reo and Mātua Whāngai, on Kura Kaupapa Māori, and the social issues that flourished towards the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s. Notable were groups like Maranga Mai (formed in 1979), Te Ohu Whakaari, Te Ika a Maui Players, and the evolving of The Depot Theatre into Taki Rua, the first theatre dedicated exclusively to work by Māori for Māori.

Jumping forward to today we find Auckland Theatre Company, our most significant government funded mainstream theatre, regularly staging Māori theatre productions – major works by celebrated playwrights including When Sun & Moon Collide by Briar Grace-Smith (2001), a stripped back version of The Pohutukawa Tree featuring Rena Owen, Witi’s Wāhine by Nancy Brunning (2023) based on Ihimaera’s short stories and featuring a wāhine Māori cast with a powerful immersion into Te Ao Māori. Alongside this were collaborations with actors George Henare, Rob Mokaraka, Miriama McDowell, Matu Ngaropo and companies such as Massive.

Tamaki Makaurau also boasts Te Pou Theatre, a kaupapa Māori performing arts venue in Waitākere, which does extraordinary work.

That’s great progress in just forty years and, given the current political environment and without being too paranoid, we will now have to work blardy hard not to take a single backward step, or we could lose the lot.

Kaua e mate wheke mate ururoa.

Tiri: Te Araroa Woman Far Walking presents a masterclass in creative harmony, a finished jigsaw where all the parts fit perfectly together.

We are drawn into the world of Te Tiriti o Waitangi Mahana, Tiri for short, played by Miriama McDowell (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi) from the moment she rises up, and passes through the cosmic doorway onto the ramp and moves inexorably down the path towards us, and we can’t take our eyes off her. She is bent almost double, all in black, supported by two sticks, an imposing figure as she wraps us in Ihimaera’s words and we eat them up like hungry tamariki.

We are transfixed as she describes the arrival of the blue-eyed goblins with the three legs and her anger is terrifying. I needn’t have worried about this audience; they are with her all the way from her first spat out angry syllables, to her sniggery chuckles about past loves and lovers, and her mourning of far, far too much loss.

She is, she tells us, one hundred and eighty-five years old, born on the day of the signing of Ti Tiriti of Waitangi, and she has a story to tell. It’s a linear history (with segues) of Aotearoa and it rips our guts out. At eighty, I’ve shared a bunch of those experiences seen through my own blue Pakeha eyes, and I’ve read about others: the assault and siege at Ngātapa in 1868, the 1918 flu epidemic that my parents lived through as kids, the injustice of The Rehabilitation Act 1941 that gave farms to Pākehā returned servicemen – my dad was one and he told the government to stick it – the Land March in 1975, the 1981 Springbok tour, until her litany became blurred with my own memories: Takaparawhau, Raglan Golf Course, the foreshore and seabed marches, the terror raids on Ngāi Tūhoe, there are plenty to choose from and McDowell is magnificent embodying each hurt with its own rough honesty.

At times, when memory fails. she embellishes her truth with wee fibs but by then she has been joined by Nī Dekkers-Reihana (Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Porou) as Tilly and they keep Tiri, to some extent, on the straight and narrow. As a double act these two are unparalleled – funny, tart, a bit bitter, angry, hurt, yet smart – and always bang on song. Tilly is an alter ego, a younger Tiri, a witness, a counter punch, and they match McDowell, blow for blow, every step of the way

I worry (because I’m a worrier) how this audience will handle the unashamed use of Te Reo Māori – it’s embedded in all the places where it belongs – but while I love it and my Ngāpuhi wāhine Plus One is happily soaking in it, I’m not sure how my middle-class pakeha audience mates will be getting on. Again, I needn’t have worried because I am surrounded by a pretty full house, a bunch of people who quite simply ‘get it’ as illustrated during the most contemporary moment towards the end of the evening that I won’t tell you about but which brought the house down with cheering, hooting, and clapping that would have resonated all the way to the Whare Pāremata in Whanganui-a Tara.

Both Dekkers-Reihana and McDowell drenched us in story, chant and song until I was happy beyond words and joyfully joined my white honkey mates in a resounding standing ovation that said, while we’ve still got to stand strong as allies and not buckle or get bored, the message to Mr Seymour and his racist mates and to Mr Peters and his coven of smug Trumpist bigots is ‘you’ve misread the mood of the motu and we’ve had quite enough of your shenanigans.’

Now I’ve got that out of my system it has to be said that clever Mr Ihimaera has set this up beautifully as every step on Tiri’s journey has been a call to arms and, while it’s certainly taken us a while, we’ve finally got the message – don’t screw with who we are as a nation, don’t you dare.

Creative harmony?

Yes, all the narratives meld and fuse into the one magnificent whole – Hakaraia’s perfectly lit imagery, Te Ura Tauripo Hoskins’ (Ngāti Hau, Ngāpuhi, Rarotanga) outstanding costumes, Kingsley Spargo’s fine compositions and nuanced sound design, and John Verryt’s excellent set right down to a simple wooden stool – all lean in on each other like the rafters of a house and support and enrich this wonderful work of art. The imagery throughout is its own narrative and the linear nature of the storytelling is embedded in all of us. We all do it as we look back and reflect on the moments – some wins, some losses – that make up our brief sojourn here on this planet, and it’s how we share these moments with whanau and friends (yes, and audiences).

There are even special bonuses – Dekkers-Reihana’s singing (they have the voice of an angel), McDowell’s unwavering physicality – all bound up in a bow by Katie Wolfe’s profoundly good direction. I know her gifted hand is all over the production, but I can’t actually see it anywhere.

Selfless stuff, Katie, thank you. From all of us.

I first heard of Witi Ihimaera at a secondary school national drama workshop in the early ‘70’s. The lecturer, long gone, gave us all a pirated photocopy of Ihimaera’s His First Ball’. I read it during the lunch break, and it sucked me in with its unrelenting innocence and charm only to then spit me up against the wall with the most gross example of casual racism I’d ever experienced. My anger was white hot but impotent. I could do nothing to fix the situation for that lovely young boy, and it felt like, at that moment, that was my only job. Next came Pounamu, Pounamu’, and I’ve been a fan ever since.

Sorry, but I can’t resist this wee digression – Tim Bray staged Witi’s The Whale Rider for kids at the Pumphouse in 2014. Tim and I were long term mates, and he invited my whānau and myself to the opening night. Our son Finn was eleven at the time. There was a raffle with a copy of the book as a prize, Finn bought a couple of tickets, and he won the book. He was over the moon with happiness, and even more so when he got to meet the author. The two of them talked together for at least half an hour and Finn has never forgotten that sublime act of adult kindness.

‘Uncompromising’ was a word I heard used more than once as I played Pokemon Go in the foyer at the end of the evening and waited for my Plus One. Yes, the work was uncompromising because every person involved knew exactly what their job was and each had the skills to make it happen to maximum effect. The script was uncompromising too, it spoke to the times, and to the history, and the performances never gave an inch. Each performance was worthy of its own accolade, and more.

A small bird told me that Witi Ihimaera’s Mum might have been the inspiration for the play. Watching TV, she apparently saw someone turn 100 and get a letter from the Queen. If she got one, she said, she’d spit on it it.

Good call, Māmā.

In the unlikely event that I get one, I’ll give it to Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke and she’ll know exactly what to do with it.

Toitū Te Tiriti

Bravo.