ANZAC Day 2022

I spent much of ANZAC Day trying to find something to commemorate among the countless lives sacrificed to the gods of money, nationalism, and ego.

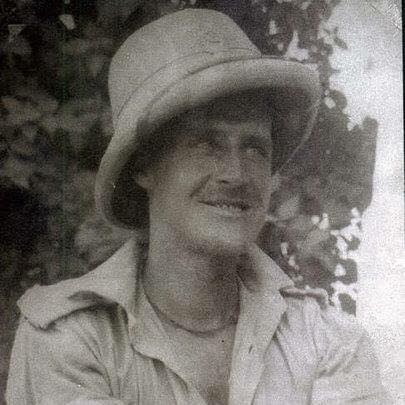

The ANZAC Days of my childhood were not the jingoistic memorialising of tidied up carnage that they are today, the knowing was still too raw and real. Some men marched. Many more didn’t. My father stayed home with his bitterness and angry confusion, and I stayed home with him. It was always a sombre day and I freely admit that it’s never got any better for me. I sat in our lounge in my place on our sofa with his medals perched next to me. I picked them up at one point with a view to polishing them, but almost immediately put them down again and they remain beside me as unattended as tomorrow’s commemorations will be.

The irony of the medals was that, while I at least thought about doing something with his, mine stayed stoically in their presentation cases totally unacknowledged. That’s not to say that I don’t value them, I do, and on rare occasions I will wear the miniature’s, but on Anzac Day I feel no need for any such recognition.

My early memories are of a Dad whose suppressed anger I did not understand. My mother seemed to, and she looked after him, kept him safe from himself, from the demons of his world. He was never angry with me as I recall, nor with my two step-siblings who he adopted and treated as his own, never with our mother whom he adored, but profoundly angry with the nameless, faceless men who he held responsible for the deep confusion he felt about what had happened to him, to those he loved and who had died or been maimed alongside him in the name of whatever history might ultimately tell us this turmoil had been about.

Or for.

Nor did I understand, for some years, where he went during his long absences, his periods in Queen Mary Hospital, and in Christchurch Public as well, for what was euphemistically called ‘shell shock’. In truth, there were times he was as mad as a snake but that’s hardly a surprise and PTSD wasn’t a condition you could claim to have even in my day. You just had to ‘man up’ and ‘bite the bullet’.

It’s always been the Kiwi way.

He was, in reality, a very unwell man who, for the remainder of his life, regularly saw a psychiatrist and had frequent periods of electroconvulsive therapy which, at that time in our history, never did anybody any good. That poor, dear man having his head blasted with electric currents and no anaesthetic in the hope that somehow this would make everything alright. Of course it never did and that fine man led a deeply disturbed life until he died, in the street, going to the shops to get dinner for his family at the age of 63.

I remember clearly the ANZAC Days from 1949 onwards and they were days of intense and all-consuming sadness. From that earliest memory up until the 1970’s there was no ‘remembrance’ as we know it today. Yes, there were commemorative services at war memorials around the nation, but most of us didn’t go to them but waited instead for 1pm to roll around, so the shops and bars could re-open and life could return to normal. More like a tight-lipped, shudder of cultural inconvenience than any sort of cherished memory.

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, ANZAC Day was most likely epitomised by Eric Bogle’s 1971 anti-war anthem ‘And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda’ than it was the endless renditions – and in many cases rendings – of the hated (by me anyway) ‘Last Post’ that we are endlessly haunted by, and taunted with, today.

Why do I dislike it so much? During my eight plus years of military service – and in particular during the three months of basic training – I was, quite simply, always in trouble. There were reasons for my odd predicament that were, at the same time, bizarre and disturbing, but also very, very funny – unless you happened to be the poor squaddie living through it in which case it was deeply confusing and bloody cruel. It’s a never-ending cycle, manipulated by the army, to ensure that troublemakers – I wasn’t one – learn to conform. It goes like this: there’s an inspection in the morning and the officer of the day inspects the barracks. My bed would be considered untidy so I would be put on CB (confined to barracks) which meant I wasn’t allowed to go any anywhere on the base until I had reported to HQ and been dismissed. The bugle would play and I would report to the regimental office and stand at attention by the flagpole in the kit I’d been told to wear in that instance (PE gear, number ones, full pack and rifle, whatever). I’d wait until the duty sergeant inspected me and dismissed me. Sometimes he’d give me jobs to do. If I was given 2 days CB I would report every time the bugle played – reveille, assembly (breakfast mess call), sick call, sometimes church call, drill call, mess call (lunch), drill call, mess call (dinner), and lights out (last post) – next day, repeat.

Sometimes I’d be standing there all lunchtime and, when dismissed, I’d have to race back to the barracks, unfed, change into the kit for the next training session, and get on parade in time, and looking good enough, to pass the next inspection. Most days I spent so much time ‘chasing the bugle’ I didn’t have enough time left to do the chores that would have kept me out of trouble the next day. Mates would iron my uniform and clean my weapon and so forth which was great – but the next day I’d get picked up for something quite different like my hair being too long or my béret not pulled on straight.

Sergeant Major: (standing behind me): ‘Am I hurting you soldier?’

Me: ‘No SarMajor’.

Sergeant: ‘Well, I should be, son, I’m standing on your hair’.

Or I’d cop it for ‘not standing close enough to the razor.’ Any reason at all and I’d be back ‘chasing the bugle’ and that went on for the full three months.

So, that’s one of the reasons I hate the ‘Last Post’ – it’s made up of snippets of each and every one of those fucking bugle calls. You hear it every night as a call to go to bed and during the rest of the day it’s demanding that you get up in the morning – ‘hands off cocks, feet in socks’ – or shouting at you to ‘come to the cookhouse door, boys’ and chow down. I was quite fortunate in that most of the time I was running around like a blue-arsed fly chasing it, it was being played on a scratchy old recording so at least it was consistent. Frankly, there’s nothing worse on the planet than hearing some kilted dipstick, who learnt to play the thing on the bagpipes at school, whining away in the sunset, or some geriatric school cadet farting and burping it out at 6am on a freezing cold, late April morning on a trumpet, a bugle, or a cornet that he hasn’t touched since 1983. There should be a law!

My Dad hated ANZAC Day.

He hated the RSA, and most of his mates did too. And they didn’t talk about their experiences at all. I asked from time to time because I was a kid, war comics were popular, and my Dad was a hero, but the subject always got changed, usually by Mum. I was proud of him being a soldier and he knew that but no stories, good or bad, were ever forthcoming.

I have no idea what my brother thought of my fathers service. He had lost his own father to some disease or other before the war – we didn’t talk about that either – and I guess he had his own shit to deal with. It seemed he had a good relationship with my Dad, though, and my big bro was my hero throughout my childhood, and beyond. He was a successful sportsman who subsequently had a fabulous business career so he had every right to be inordinately proud of what he’d achieved and my Dad stood with him all the way.

My sister always had a particularly overt attitude to men in uniform whether it was a piper in a highland band, a naval officer in his pristine whites, or a soldier in whatever uniform happened to be on the go at the time. She was immensely proud of my Dad right up until the day she died and they were always close. I don’t think she had a clue what his experiences had been and, to some extent, that doesn’t matter. What matters is that she thought highly of him, respected him, admired and loved him as the man who was her father.

My relationship with the uniform is far more complex. I always saw it as a means whereby I could prove my masculinity and it took many years for me to actually step back far enough to see that my life, until that moment, had been peppered with experiences that I had designed exclusively to that end but which were self-deceptive and ultimately self-destructive. My mum knew what that was all about I have no doubt. More about that another time.

Perhaps.

Dad was in the heat of battle for four years. He’d been a very good rugby player and was, I suspect, an alcoholic. You’d think those ‘qualities might qualify him for an RSA life membership sustained by days holding up the bar but, in truth, he wouldn’t go near one. Nor would he, after the first couple of years, march in a parade. On the rare occasions that his life touched any of that returned services nonsense he’d cryptically suggest that the members of the association, and those who marched, were never ‘the ones who actually served’. It’s not what he meant, of course, he meant that the men with whom he would have been happy to march were all gone, dead in ‘some foreign field’, and that his well of pain was just too great for it ever to be possible to willingly revisit those days and the memories of those dead young men. He did say once, that , quite early on, he had become the last surviving member of his original platoon and that, after realising that, he had stopped making friends because the reinforcements were poorly trained and mostly didn’t last long. His greatest fear, when my number came up, was that he’d have to bury me and I don’t think there was any way, knowing what he knew, that he could have ever lived with that.

It doesn’t take much to work out why my father was not only a passionate pacifist but an outspoken and vocal one to boot. I was too, I need you to know that, and to also know that I still am. I have actually been a passionate, anti-war activist all my life and I don’t see that changing any time soon but the rifle is a sexy and seductive beast and alongside the threat of imminent ‘death in a ditch’ and powerful peer pressure to man up, can bring about a fairly rapid compromise. Not a change in values or beliefs but more an expedient and situational, survival-driven, change of heart.

I registered as a conscientious objector when my number came up – don’t believe what governments like to tell you when they say that we’ve never had conscription in Aotearoa because we have, we had a vile form of enforced service that involved pulling birthdays out of a hat. Not every young man had to do their ‘it’ll put hairs on your chest’ military training, only those who happened to have unfortunately placed birthdays. Mine – the 17th – was particularly unfortunate because the 16th and the 18th were drawn as well. No way I was going to get out of that lovely little lottery. Compulsory military training was considered vital for every 20 year old, able-bodied, young male person after WWII – we also had compulsory ‘cadets’ at school – but by the ‘60’s, with the Korean War, the Malayan Crisis and subsequently Vietnam, sucking away our young men, the appetite of the people of Aotearoa for participation in what seemed like an endless diet of useless wars was waning and the lottery process was intended as a sop to the warlike to somehow keep it all going because, after all, ‘we mustn’t lose face, old chap’. It didn’t save it, of course, and a few short years later it was scrapped and replaced by the voluntary Territorial model that still exists today.

A pyrrhic victory, I’ve always thought, for the sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll generation.

The army considered my request for Conscientious Objector status but rejected it because, as my father had been a decorated serviceman, it wasn’t conceivable on any planet that they knew of for the only child of Pte John ‘Dillinger’ Matheson 10486 to be anything other than the ruthless killer their father had been. So, despite a letter of support from my Dad and Alban Purchase, the local vicar, the answer was no. Not great logic, but when it comes to the army, logic has never been its strongest suit.

I won in the end, though, simply by refusing to be issued with a weapon which might explain why I was dumped into the medical corps with all the other Klingers, queers, pooh-pushers, and malcontents. They gave us IQ and aptitude tests and I passed them all with scores that surprised everyone, including me, but I was never chosen for officer training and when I had the temerity to ask why I was told that I could never be trusted as an officer in ‘this man’s army’ because I simply wasn’t capable of ever following orders.

They might, perhaps, have been right because, by the time I finished my three months basic training, I was in trouble again, this time for refusing to sign the Official Secrets Act. I wasn’t alone, a number of us refused to sign regardless of the threats that were made. There were somewhat veiled threats of courts martial and far more tangible threats of time in Ardmore Military Prison because we had been shown material about the horrors of Vietnam that should never have been shared with recruits in training or anyone not, at that time, bound by the Official Secrets Act. I imagine somebody’s head rolled for that but we didn’t care about the threats, we simply said no.

Around that time I talked it over with one of my officers. He had invited me and some mates to bring our guitars and to entertain in the Officer’s Mess. We had a band that wasn’t half bad. After a few drinks I got up the courage to ask him why was it such a big deal and why couldn’t they just trust us to be honourable and not go to the media with the material we had been shown. He was shocked, stunned that soldiers might suggest that they could be trusted without first signing a piece of paper. Maybe coincidentally, but the demand that we sign the Act – and the threats – seem to just drift away. I can’t speak for the others, but I never did, and never have, signed that Act.

After our three months basic training we were all deployed to our specialist units and I went, first to 3 Field Ambulance which provided regimental aid post services – the mud, blood and shit brigade – which was based at Burnham. and then, when I moved to Wellington, to 2 General Hospital which was based at Wellington Public Hospital where we emptied bedpans and mopped floors. I’ve always suspected the staff didn’t have much time for us squaddies so they made life as unpleasant as they could for us. The dudes on periodic detention got a better deal than we did and the only things I learned in the entire two years were humility and, more importantly, where Nurse Jarman lived. The latter, I must say, made the whole farcical episode totally worthwhile.

I was never issued with a rifle and there was no demand made that I ever carry one after my basic training was finished. A year or so later, in the middle of a camp at Tekapo, the new government changed the law and we conscripted canon fodder were no longer required to see out our military commitments and most left immediately. I shocked all my colleagues, and myself, by signing on for a further five years. Virtually everybody else in my unit told the army where to stick it and left without ceremony. I’d actually begun to enjoy it. Running a field hospital deep in the bush can be exciting and doing good works has always been a bit of a thing for me. Even if all my clients were bleeding and sneezing and riddled with the pox.

I’ve never regretted the decision to re-sign because, not long after that, I moved to Taranaki where I was seconded to the Taranaki regiment, a regular force unit. The guys were fabulous and looked after me even when we were deployed to Vietnam. To my knowledge I was the only volunteer territorial in the country who was given their orders to ship out and, when I asked why, I was told your unit want you with them. I was touched by that because, compared with those guys, I was no great soldier. They looked after me really well and I guess they knew I would look after them when the shit hit the fan. There was never any doubt we had each other’s backs. Some of these guys were going back for their third tour so they knew what we were in for and I was certainly well briefed. Our training was good but nothing like the real thing. We’d hit the bush for weeks at a time and sometimes I wouldn’t see them for days. When they reappeared out of the mist they always had great kai – pork, venison, kai moana – and they relied on me to have the beers and the chocolate.

It was around that time that I decided this non-combatant thing that I was so proud of – ‘the medic without a gun’ – was actually a crock of it. I got myself issued with a weapon and convinced myself that I did so to enable me to fulfil my duties as a medic and properly protect my wartime patients. During the dark nights of the soul, however, I was a bit more honest with myself and owned up to the fact that if the bastards were going to shoot at me I wanted to be able to shoot right back. That’s how naïve I was. Regardless of my training, I really had no idea what jungle warfare for a medic in Vietnam would really be like.

I do now.

So there was a lot of reflection over the past weekend for me, about Anzac Day, about my own experiences as a soldier, the good, the bad and the manic, my lovely Dad and Mum, and it’s probably best for everyone if I just leave it there.

The ANZAC Day evening in 2020 was interesting.

After a lovely dinner which involved a delicious entree of dumplings and a main course of chowder and later in the evening ice cream for dessert, we watched one of the best episodes from an earlier series of ‘Brokenwood Mysteries’ and followed this up with Episode One of a new New Zealand series called ‘One Lane Bridge’.

‘Brokenwood Mysteries’ is an exceptional piece of work with good scripts and superior acting from what is a rather experienced cast. There’s a hint of ‘Midsomer Murders’ about it, but that’s hardly a bad thing. In part I enjoy it because I’m a great fan of Fern Sutherland whose work is subtle, nuanced, honest, and incredibly consistent. She sets the bar high but most of her colleagues reach it as well.

I’ve got a bit of a thing about an exceptional character who occasionally shows up in New Zealand films and on our television and that character is the unique New Zealand landscape, ‘Vigil’ and ‘The Navigator; a Mediaeval Odyssey’ being probably the best examples. Both ‘Brokenwood Mysteries’ and ‘One Lane Bridge’ highlight the land we live in and allow the often brooding landscape to take its toll on us. I was especially impressed with ‘One Lane Bridge’ because, without the menacing landscape, there would’ve been no ominous backdrop to this extraordinary Pip Hall and Philip Smith story.

There was another COVID-19 death that day but only five new infections so, while it’s always an unhappy occasion when we add to our death toll, we can at least hang our hats on the fact that, at that time, we’d flattened the curve and that the future looked relatively good. I remember thinking ‘I doubt the new normal will look anything like the old normal’ but I sincerely hoped that we could retain the environmental benefits that seemed to be accruing from sticking to our guns and just staying home.

So that day was full of love and painful stuff.

This year, it’s just the pain that’s survived.