Power Ballad

Created by Nisha Madhan and Julia Croft

Performed by Julia Croft

Produced by Zanetti Productions

At the Basement Studio, Lower grey’s Avenue, Auckland

Tuesday 06 June, 2017 to Saturday 17 June, 2017 at 6.30pm

Julia Croft is a fact. ‘Power Ballad’ is a feeling.

Confused?

Experience Croft’s dazzling performance and all will become clearish and you have until 17 June to do so. If you’re a consumer of the extraordinary and lap up new challenges, this is a show you’ll cherish – but leave your expectations in the bar because you’ll have no use for them in the Basement Studio because, if there is one thing Croft and Madhan do exceptionally well, it’s defy expectations. In fact they eliminate them altogether, and that is wildly exciting. Croft is a sublimely good communicator who has no fear of the new and who has a performer’s toolbox she’s barely broken the surface of. We, who sit in the dark, know there is so much more to come and I for one want it all – and I want it now!

Not that I’m dissatisfied with ‘Power Ballad’, quite the opposite, but I want what Croft the performer does to me because she, in no short order, reminds me that even the most complex of ideas can be performed in ways that make ideas themselves seem chaotic, borderless and yet eminently accessible. It’s a gift few have, but the partnership of Croft and Madhan has it in plenty.

In short, ‘Power Ballad’ has at its core the profound feminist issue of communicating while using the language of the patriarchy, the oppressor and of oppression. In her marketing Croft quotes Kathy Acker, the American novelist, punk poet and sex-positive feminist, who wrote “I am looking for a (body) language which exists outside the patriarchal definitions. Of course that is not possible. But who is any longer interested in the possible”. Not Croft, I’m happy to say.

She goes on to describe her work as “part performance lecture, part karaoke party.” ‘Power Ballad’” she writes, “deconstructs gendered linguistic histories and rips apart contemporary language to find a new articulation of pleasure, anger and femaleness. From this era of Trump and Prime Ministers who don’t know what feminist means comes an angry, feminist, live art investigation of language and it’s sometimes hidden ideologies.”

That’s exactly what the production does – and does brilliantly.

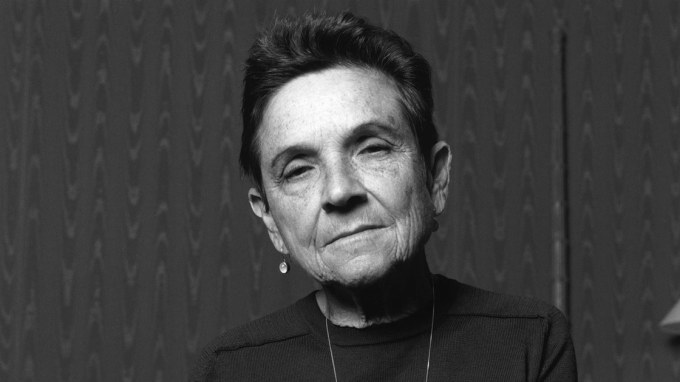

Adrienne Rich

What Croft and Madhan don’t say is that this is also a deeply intellectual work, a work that stretches the mind and welcomes us into new spaces by behaving in rare and exciting ways. You don’t have to define yourself as a feminist to engage with the work but you do have to be prepared to view communication and language through a different lens, a lens that magnifies and confuses in the same way seeing an ant magnified 10,000 times will make you feel. You know it’s an ant because that’s what you’ve been told but, hey, this is ant like you’ve never perceived ‘ant’ before. Don’t be fooled by the intellectual nature of the work, though, and expect that, because of this, it will be dry old rope. Remember what I said about expectations? It’s hugely entertaining as well because … well, because Croft.

‘Power Ballad’ is an excellent example of intellect, knowledge, understanding and top quality performance all coming together in an orgasm of delight that has the potential to astound you. Well, it astounded me to the extent that my legs were decidedly wobbly as I tootled down the stairs at the end of the performance back to my comfy chair in the dimly lit foyer and it wasn’t just decrepitude I can assure you.

So just what is the backstory of ‘Power Ballad’? It would appear to find its source in the writings of a range of literary, academic and activist feminist luminaries that is, in my view, a collection second to none. It consists of, but is not exclusively, Tyler Bradway, Adrienne Rich, Acker herself, Bell Hooks, Kimberle Crenshaw, Amy Cuddy and the inspirational and largely misunderstood – but not by Croft – Audre Lorde.

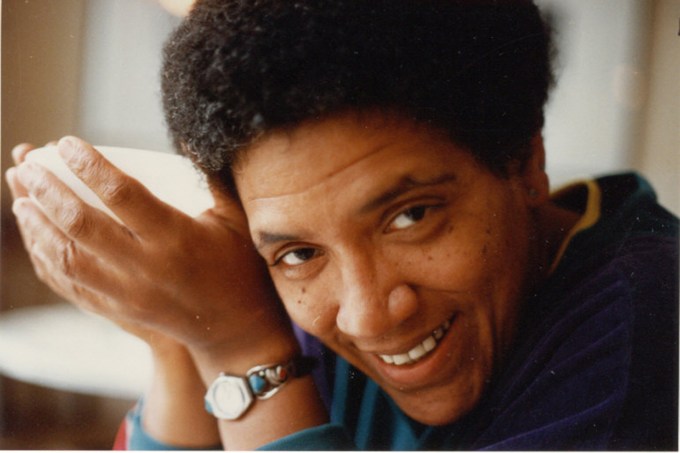

Julia Croft

Lorde, a writer, lesbian feminist and civil rights activist, is quoted in the tiny programme twice. ‘Women are powerful and dangerous’ is the first one. Forget that at your peril. The second ‘for the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change’ is key to what Madhan and Croft have in mind for us with this challenging work.

Audre Lorde

It may be worth looking at the entire quote because it expands on the idea of disruption and anchors itself in action. Lorde wrote, “survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.” ‘Unpopular and sometimes reviled’? Artists know what that feels like when they push the envelope. Reviewers too. Women ‘who still define the master’s house as their only source of support’? Look no further than the current White House to see this being played out on a daily basis!

Lorde’s discourse allied white liberal feminists with white male slave-masters, describing both as ‘agents of oppression’ and that’s heavy duty stuff, even today. Make no mistake, Croft and Madhan’s work is in the same mode. It’s powerful and takes no prisoners. Lorde said (to white feminists who claimed ‘suffering’ united the tribe) “what you hear in my voice is fury, not suffering, anger, not moral authority”. ‘Power Ballad’ exemplifies the same.

Nisha Madhan

Lorde is often misunderstood, in particular by white, academic feminists, but Croft makes no such mistake. Lorde did not ‘intend to develop a reactionary weapon against revolutionary experimentation’, quite the opposite. She would have delighted in Croft’s deconstruction of the ‘master’s language’ because, like Croft, Lorde attempted to create an ethical code that would ‘overthrow the status quo’. Her concern was that women could not disrupt their oppression using the logic that justifies that oppression’. She asked, “what does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow perimeters of change are possible and allowable.” Croft, I’m more than happy to say, gives Audre Lorde back her voice. Lorde wants women to stand up, ‘to break the false consensus that limits their options and to act boldly’ which is exactly what Croft does. More than boldly, in fact, the communication tools Croft evolves with her voice distorter, her unconventional text and her remarkable talent are at times outrageous, at times angry literally beyond words and at others wildly, hilariously funny. It takes a lot of guts to work yourself to a point where you can deliver a line like “and the streets will run red with the blood of straight, white men” and even have the straight white men in the audience lining up to volunteer their services.

Kathy Acker

Acker’s investigation into an alternative language of the body appears to be profoundly influential in Croft’s work. Tyler Bradway in “The Languages of the Body: Becoming Unreadable in Postmodernity” traces artist Acker’s journey from deconstructive aesthetics toward a “sensuous ‘language of the body’, which she hoped would make her texts ‘unreadable’ within the established hermeneutic frameworks of postmodernism.’ In “Bodies of Work” and “In Memoriam to Identity”, Bradway discloses how Acker’s conception of “bad reading” — in which “literature stimulates a masturbatory encounter with queer becoming — recovers the political agency of queer aesthetics”. Croft, in her reinvention of the physical language of performance, does the same.

Acker, like Croft, considered the prospect of a non-authoritarian language, a language of “silences: secrets, autism, forgetting, disavowals, even death” and Croft, cleverly, achieves five of the six missing only the final curtain. Acker looks for the “language of silence” Bradway muses, “so that we can hear the sounds of the body, the sounds of the unknown”. Croft, too, lives in that silent space.

Bell Hooks

Bell Hooks reminds us, via Adrienne Rich’s seminal poem “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children”, that “this is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you” and thereby lays down a challenge for Croft to respond to. Hooks says “words impose themselves, lake root in our memory against our will. The words of this poem begat a life in my memory that I could not abort or change” and, referencing this, Croft sets out to disrupt and deconstruct our understanding of standard English and generic communication and to rupture and recreate a new and independent patois of a unique, dispossessed and displaced people – us. Hooks is smart enough to know that it is “not the English language that hurts, but what the oppressors do with it, how they shape it to become a territory that limits and defines, how they make it a weapon that can shame, humiliate, colonize.” Crofts is smart too, and uses this to her – and our – advantage. It’s as though Hooks, perhaps inadvertently, gives Croft permission to selectively use aspects of the language she most wants to avoid. Rich says “this is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you” and, as it turns out, she is so right. Artaud went further. ‘Burn the texts’ he said, and Rich agrees. American social psychologist, author and lecturer Amy Cuddy is pretty succinct as well. She says simply ‘our non verbals govern how other people think and feel about us’ and Croft’s non verbals absolutely blow us out of the water.

Tyla Bradway

Tyla Bradway

So, is there a narrative?

Yes, there is, but while it slides easily in and out of expressionist mode, it’s easy enough to follow and to engage with. Well, I found it so anyway. Croft manoeuvres us deftly through a journey from speechlessness to something else with only the help of a microphone and her handy voice distorter which she uses with extreme dexterity and skill, changing and adapting vocal sounds, body percussives and environmental scrapes and scratches and by looping, adjusting and evolving her own unique personal soundscape. It’s fascinating, clever and visceral, its sexual, sensual and delicious, it’s funny, angry, wild and punishing. The audience gets to watch and listen to all this and we get to sing too. This truly surprised me and I found myself gurgling along to KaraFun.com and feeling totally engaged with what this dazzling performer was expecting me to do.

Ann Cuddy

So what is it you’ll experience when you buy a ticket for ‘Power Ballad’? Pure performance art delivered by a superbly talented artist, profound art that challenges and is anchored in an intellectual discourse for the ages that is really hard to beat.

I adored Croft in ‘If There’s Not Dancing at the Revolution I’m Not Coming’ and, if anything, ‘Power Ballad’ is even better. ‘Power Ballad’ has been selected to travel to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and your ticket price will help make this happen. If you didn’t see ‘If There’s Not Dancing at the Revolution I’m Not Coming’ the first time around you’ll get another chance from 8 – 10 and 15 – 17 June at the Basement Studio at 8.30pm. See both. Live dangerously. Enjoy the leaf blower too – there, you have something of a spoiler (but not really). ‘Power Ballad’ comes with a nudity (well, semi) and language warning but you’d have to be a prude of the first order to ever be offended by it.

And you’re not a prude, are you?