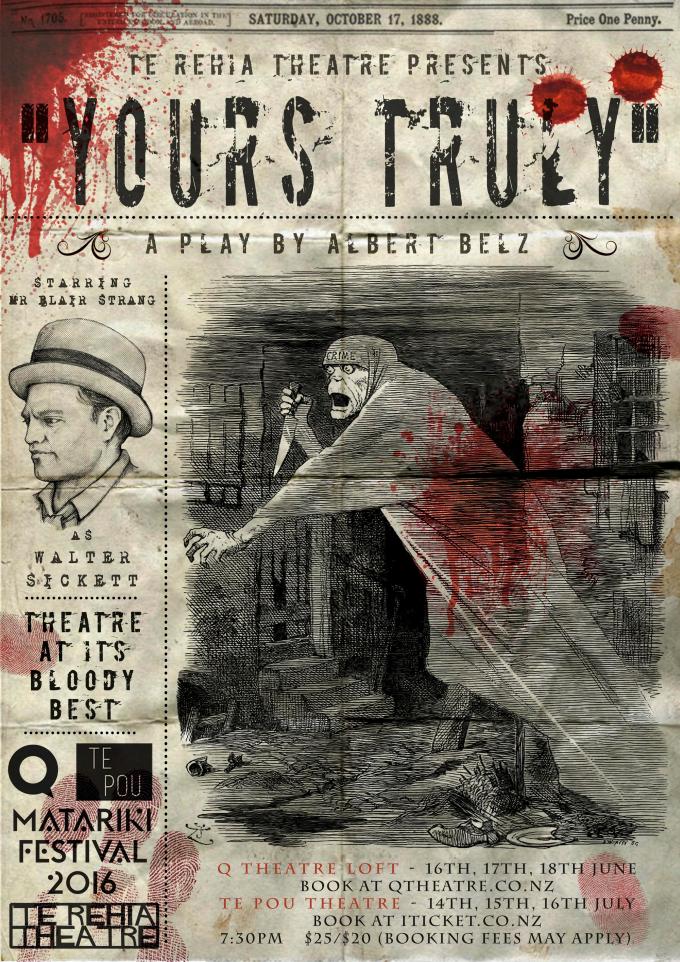

Yours Truly

Written and Directed by Albert Belz

Produced by Amber Curreen and Ascia Maybury for Te Rehia Theatre Company

Lighting Design by Tim Williams

Sound Design by Rory Drew

Set and Costume Design by Ascia Maybury

At Te Pou Theatre

From 14 to 16 July, 2016 at 7.30pm

Enfant colère jeter Sam Brooks threw his crayons out of his cot early this week with a pétulant article in ‘The Spinoff’ entitled ‘Critic’s Day: A professional theatre critic explains why New Zealand theatre criticism sucks’ and in it he’s had a hack at everyone whose work he doesn’t like – mine included. I write ‘three thousand word essays complete with footnotes that nobody has the time or passion to read’ and I also qualify apparently as ‘ill-informed’ and ‘ill-suited to the task’. He reiterates his loathing for Theatreview – nothing new there – acknowledges his friends James Wenley and Matt Baker from the excellent ‘Theatre Scenes’ but ignores all other contributors some of whom do a grand job. He’s rich in his praise of NZ Herald reviewers Dionne Christian and Janet McAllister while ignoring the most perceptive of the critics at the Herald, Paul Simei-Barton. Brooks, an occasional reviewer for ‘The Pantograph Punch’ is lyrical, however, in his praise of Metro’s Simon Wilson with whom he ‘is never disappointed’ and whose reviews are ‘a genuine pleasure to read’.

Sam Brooks

A self-described ‘professional theatre critic’ – he apparently gets paid for his occasional reviews in ‘The Pantograph Punch’ – Brooks cut his reviewing teeth writing for The University of Auckland student association magazine ‘Cracuum’ less than five years ago around the same time his first theatre work was staged. Brooks seems to have a particular issue with reviewers – apart from himself, of course, and those listed above – being ‘obsessively nice’. Sam – and I say this lovingly – has only reviewed ten of the thirty six shows covered this year by ‘The Pantograph Punch’ but snippets from five of these reviews give the lie to his belief that it is only ‘others’ who succumb to this ‘oppressive niceness’ – if interested, please read on. If not, please move on to the review proper.

Brooks describes Silo Theatre’s ‘Medea’ as a ‘brilliant production’. ATC’s ‘Bloody Woman’ has, according to Brooks, ‘a tremendous cast’ because ‘Auckland Theatre Company know how to do a great musical.’ Of ‘Puzzy’, staged at The Basement during the Pride Festival, he thunders ‘it’s a joy to watch the entire cast’ and this joy remains unabated, despite his impassioned reproach that The Pop-up Globe stole audiences from the more legitimate Basement Theatre, as he observes that ‘it’s a joy to see a show like Titus return. It’s as necessary and risky a Shakespeare production as I’ve seen’ he says, ‘and one that is truly worthy of the text’ – mangled from Shakespeare’s original though it was, and better for it. Finally he tells us sagely that the Auckland International Arts Festival production of ‘Tar Baby’ does what all good theatre should do, and it does it better than almost anything I’ve seen.’ All ‘obsessively nice’ stuff I’m sure you’ll agree and in most cases I have to say I thoroughly agree with him, so, yes, Brooks is as likely as any of we lesser mortals to reach into the cookie jar of praise and to spread it liberally about.

Brooks goes on to say that it’s vitally important that they (his readers) trust that he’s giving his honest opinion. ‘When a culture is choked by the twin leashes of oppressive niceness and under-investment – both in time and money – it’s impossible for it to thrive’, he says. ‘And when the critical culture isn’t there, the art form in question can’t achieve to its true potential.’ Who could disagree, certainly not me, but to presume that others are being dishonest based solely on the fact that they disagree with what Brooks feels about the same show can only be viewed as both arrogant and narcissistic.

Simon Wilson

Brooks tells us that ‘the function of a critic is to serve as a conduit between a piece of work and its audience.’ I would add, whether present at the performance or not and suggest that this is already what we all do, Sam Brooks included. ‘The function of a review’ he continues, ‘is to be the first word in the conversation, not the last one.’ Again, I would agree, and the opportunity to engage further in this discourse is available, and regularly used, by readers at the Theatreview site. Ironically, Duncan Grieve of ‘The Spinoff’ has since discontinued the comments section of his site thus unceremoniously ended the brief but polite discussion of Brooks’ article that developed there. I have to admit that, try though I might, I cannot connect Brooks’ definition of the function of the critic, his belief that the conversation should continue and his assessment that, as a result of this non sequitur, ‘theatre criticism in this country is fucked’. It simply doesn’t make sense. I also don’t think it is fucked, nor do I think his rant will help improve things one little bit.

It’s true, most of us don’t get paid and we can be described, using Brooks’ dismissive term, as ‘hobbyists’ yet ‘professional’ itself is a seriously loaded term. I was paid for my reviews for many years. Was I a ‘professional’ theatre critic then? Am I now? Does the term ‘professional’ link to payment or simply to a quality gained by experience?

This discussion has cropped up spasmodically throughout my forty six year theatre life and it isn’t about to end any time soon. It might be new to Sam but this doesn’t make it new to all of us. Nor does the fact that it’s a cyclic thing discredit Sam’s opinion. I value the debate, I welcome it, I just wish the discourse had been better structured, less self-aggrandising and sycophantic, far less bitchy and much more constructive. On the other hand, it’s a re-igniting of the discourse and that’s a good thing. Personally, I couldn’t care less what Sam Brooks thinks of my work. I’m comfortable that I fully research my reviews, contextualise them, and say what I think honestly. If I say I liked a show then I did, regardless of what the boys in The Basement bar might think when in vino veritas. I think it’s absolutely great that they love to talk about the theatre and have strong opinions but I feel no more obligation to be influenced by them than by anyone else. My reviews are my opinions – hopefully informed – not anyone else’s. If I quote anyone else’s opinion, as I sometimes do those of my son, I’ll reference or acknowledge it.

There, that’s an end on that.

Albert Belz

Let me be clear from the outset. I am an unashamed fan of the work of Albert Belz (Ngati Porou, Nga Puhi, Ngati Pokai) whose career began with a bang in 2001. His debut, full-length play ‘Te Maunga’ was a critical success. ‘Te Maunga’ was followed by a stint scripting ‘Shortland Street’ to keep body and soul together and to hone his already considerable craft. His second script for live performance was, in my opinion, one of the great New Zealand plays. ‘Awhi Tapu’ was nominated for a number of Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards and, in 2006, ‘Yours Truly’ won awards for ‘Best New, New Zealand Play’, and ‘Most Original Play’. The exotic ‘Raising the Titanics’ toured New Zealand and ultimately won ‘The New Zealand Listeners Best New New Zealand Play’ award for 2010. A popular writer for children, Belz’ play ‘Maui Magic’ was a huge success in the City of Sails and beyond. Belz has worked as Story Editor with Red Leap Theatre and has had residencies as Writer-in-Residence at Waikato and Victoria Universities. So, yes, he’s been around.

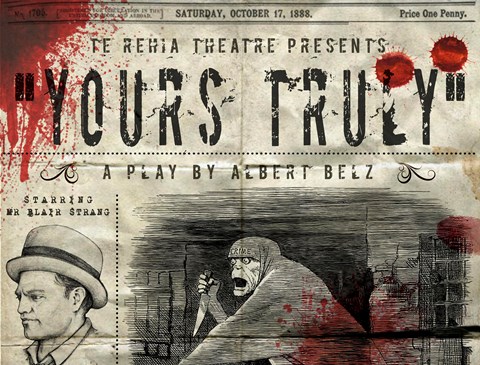

Taking our seats in the Te Pou auditorium we are immediately confronted by five floor-to-ceiling, sepia coloured, hand-painted portraits of naked women. They are surprisingly beautiful. It’s clear from the delightful, hand-bloodied programme, the effective advertising and the many past productions of this well-aired work that this play is about Britain’s most notorious serial killer Jack the Ripper so the naked women come as no surprise. Nor does the style of the hangings, a chic that clearly links us to that most easily recognized period in British history and all the mythology that surrounds the Ripper himself.

I believe I was wise to have my thirteen year old son Finn with me as he is steeped in the minutiae of Ripperology, a fascination that, from time to time, borders on the obsessive. Mind you, he has over one thousand Pokémon cards as well and can tell you everything about each of them so I doubt this Ripper thing is really anything for me to be concerned about. It’s simply a never ending quest for arcane knowledge and who can take issue with that? A recent visit to London included a walking tour of the Ripper’s Whitechapel hunting ground hosted by Auckland actress and close friend Charlotte Everett ending with dinner at The Ten Bells Public House where the Ripper’s victims were known to sup. We also visited the London Dungeon where we met not only Jack himself but Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and both had the air of absolute terror that history has imbued these stories with, one true, the other fictional, both as scary as hell itself. Finn informed me sagely, when I told him of the play, that its title, ‘Yours Truly’, is part of the signature on the chilling letter supposedly sent by the Ripper himself to Scotland Yard. ‘It’s a clever and subtle touch’ I am informed by this excited young man. This, plus my own obvious fascination with the case, seemed to equip us well for the evening ahead.

Ripperologist Finn Matheson

As with the London experience, this production opens with that same air of trepidation via a pre-recorded soundscape of text snippets and evocative but non-specific sound that is overlaid with phrases such ‘as do you like women’ and ‘all they did was kill’ repeated, along with others, until we were more than ready for the sounds to stop. The effect was electric and took us instantly from our miserably stormy surroundings to the even darker underbelly of Queen Victoria’s London and, even more precisely, to the dingy streets of 1880’s Whitechapel and Spitalfields.

The production is smart and the theatrics are effective throughout. There’s a trick with a match that is repeated to increasing effect and Belz’ dazzling text astonishes at every step. It’s articulate, rhythmically remarkable, intellectually exhilarating and replicates all of the cadences we recognise from writers of the period such as Wilkie Collins, Thomas Hardy, Anthony Trollope and others. In seconds Belz has located us in time and place. The excellent costumes (Ascia Maybury) contribute significantly to the character of the work and considering that this is not a funded production the visuals are that much more impressive

.

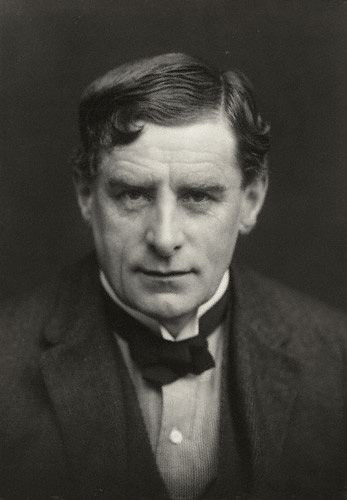

Belz has taken a thought-provoking slant on the few known facts of the Ripper case. We still don’t know who this evil genius was and everyone from Patricia Cornwell, Christchurch-based actor and director Martin Howells and acknowledged experts such as Richard Jones, Alan Drake, the great Donald Rumbelow, William Beadle, Russell Edwards and Stewart P Evans has a passionately help opinion but no-one has proved definitively whether it was indeed Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward, Duke of Clarence, painter Walter Sickert, writer Lewis Carroll, Lord Randolph Churchill, Mary Pearcey (Jill the Ripper), Francis Tumlety, Aaron Kosminsky or someone altogether different who was the killer. Belz has his opinion and it all fits together very nicely in less than two hours, interval included. The large house on opening night certainly seemed thoroughly engaged as indeed was I.

Donald Rumbelow

Belz has taken some key personalities – artist Walter Sickert, himself often seen as a suspect, Ripper victim Mary Kelly, Prince Eddy Victor the ne’er do well grandson of Queen Victoria and namesake of her own beloved husband Albert, Governor of Guy’s Hospital and Physician-in-Ordinary to the HM Queen Victoria herself Sir William Gull – and brands, with shock, awe and absolute authority, the latter as the guilty party. I can find no tangible evidence beyond a Masonic Lodge/Royal Conspiracy theory posited in a book or three and a film or two in the 1970’s but this should come as no surprise as new candidates surface each and every year, the latest being Francis Spurzheim Craig, ex-husband of victim Mary Jane Kelly who was identified as recently as 2015

It’s Belz’ handiness with the script that makes the whole thing work and provides the audience with a more than satisfying – and challenging – evening’s entertainment. It’s to Belz’ credit that at no time did I question the veracity of his ‘facts’ and the pseudo-mockumentary nature of the presentation fully supported this. It’s canny stuff, totally enjoyable and full of revelations of varying scale and magnitude.

Stephen Brunton

There are scenes to delight throughout. Stammering Eddy meets sweet-selling angel Annie Crook, a lolly-shop girl selling delicacies from a tray in the street, and falls instantly in love with her. I do too because Esmee Meyer’s turn as the ill-fated Annie is quite simply splendid. She’s just cute enough, just clever enough, and just honest enough to convincingly win the heart of her wide-eyed prince Eddy Victor (Ben Van Lier) and the entire audience. There’s the most delectable word-play around toffs and toffee, sweets and sweethearts and we are all fittingly drawn into it. Eddy’s mate, Walter Sickert (Blair Strang), – we never quite know why they are friends, perhaps he’s the royal ‘minder’ – lies about their relationship saying they are brothers but no one, certainly not Annie, is taken in by this pretence.

Mary Jane Kelly

There’s a Holmes and Watson relationship brewing between Sickert and Eddy rather like the one between Downey Jnr and Law and it’s more than a trifle attractive. There’s nothing quite as exciting as seeing two actors enjoy the trust inherent in a great working relationship. We are introduced to the rhetoric and form of Masonic ritual and the words of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘Aurora Leigh’ while Eddy asks Walter if he and his artist’s model friend, prostitute and paramour Mary Kelly have yet ‘made the beast with two backs’ and we know without a doubt that, with Belz, we are in super-cultured country indeed. Belz’ own script is in no way secondary to the richness of its sources and we are carried along by a deceptive romantic lyricism which plays against the horror of the primary narratives being laid out before us as we go.

Sickert begins the play as an enigmatic figure and remains largely so throughout. As the relationship between Annie and Eddy progresses we learn that ‘grandmother will need to be told’, that Mary Kelly has come to see herself as Walter Sickert’s muse, and we begin to observe a side to the artist that gives us cause to wonder just what’s what. It’s not surprising since Sickert is a renowned painter of the nude female form – we’re surrounded by them – to see Mary Kelly strip down to the buff but what is unanticipated is the unapologetic, sado-masochistic nature of what the artist has her do with her scarf. With so many of the Ripper’s victims strangled from the front … but, tantalised, we move on.

Plays presented as ‘Yours Truly’ is in a series of episodes often have scenes that are notoriously difficult to end and then segue smoothly into the next, but scene endings, transitions and new beginnings present no difficulty to Belz who seems to have a craftsman’s grab-bag filled with a never ending bunch of very effective options. Needless to say the productions flows beautifully.

Three months into their relationship Annie lays down a challenge to Eddy when she confronts him with ‘what does your room look like’, a question which, if answered truthfully, would both expose his identity and set up the next phase of this intriguing scenario. When he vacillates she smacks him between the eyes with ‘I need to know whose child is in my belly’. In a play full of surprises this is one of the best and it propels the narrative forward with the power of a slashed jugular towards its inescapably bloody conclusion.

Blair Strang

The secret wedding between the two is a strangely beautiful affair and it’s not just a gorgeous dress that catches our attention but the convincing manner in which these two fine actors project the love they feel for each other across the footlights. The lovers head to Paris but Sickert the piker wishes to stay in London with Mary Kelly. We hear that the royal family have been told of Eddy’s indiscretion and, as expected, they are less than chuffed about it. Why you may ask? ‘Because his grandmother is Queen fucking Victoria’, Sickert reminds us, as if we could ever forget. This is the first of Sickert’s vicious betrayals but not his last and we wonder why he’s done it at all. Just what is going on in Sickert’s own backstory we ask, but there is no real answer? We knew already that the sharing of this explosive knowledge would cause chaos with the lovers but the real significance of this becomes manifestly apparent and the impending danger to Annie and her child is palpable.

Walter Sickert

Walter isn’t enjoying this one little bit because, he tells us, ‘he does not like to be surrounded by walls’. When Annie discovers the truth she too is shocked. ‘Eddy lied to me’ she complains plaintively. ‘It’s what his family does best’, the cynical Sickert knowingly replies.

By means of a most effective solo scene, presented in seminar form as though we are an audience of innocent surgical trainees, we meet William Gull, Physician-in-Ordinary to the Queen herself. While he lectures us on the vagaries of the human brain he shares with us that he, himself, is only interested in the woman’s side. It’s a strangely disturbing exercise as we hear his matter-of-fact description of the dissection of the brain within which Belz has created a rich and timely psychological study of this mesmerising and worrisome man. As psychopaths go, Sir William Gull is right up there, and any male actor looking for a contemporary audition monologue with a real difference should not look past this one because it really is a wee ripper. It has resonances of Stoppardian outrageousness with a screaming echo of silent lambs to boot.

Romy Hooper

Annie is hustled off to an asylum, her baby is removed from her and Mary Kelly, along with her new sidekick Harvey the hopeful lover (Romy Hooper), hatch a preposterous plan to blackmail the royal family. The honeymoon is over, Gull has Annie locked up and Mary’s dream of Harvey’s Haberdashery is hatched. Harvey and Mary tinker with a Ouija board only to discover that ‘there is something evil in here, something evil’ and only the interval rescues us from a fate worse than incredulity.

Always good, the production kicks into a special extra gear with every two handler scene and the second half starts with a cracker when Eddy visits the asylum and finally meets up with Annie. Eddy doesn’t cope and runs off leaving us with the newly knighted Sir William Gull who, having educated us as to his adoration of the female brain in the middle of Act One, now proceeds to do the same with Sickert only his repetition takes on a disturbing tone. ‘The mind of women fascinates me’ he intones amongst some seriously troubled Masonic rambling. The discourse between the two is fragmented and discordant and the two men do not connect at all while the actors do. It’s courageous playwriting and in the hands of these two capable actors the disconnect is most effective. It’s almost as though Gull is testing Sickert to discover whether he too is a Mason and therefore a mea culpa member of ‘The Brotherhood’.

Sir William Gull

We are introduced to the Fly Game with its ‘rock paper scissors’ hypothesis of ‘defeat me’. It’s a slight but effective device and when reprised later in the play becomes powerful beyond words. Through this we learn that the enigmatic Walter is not the powerful force he thinks he is. ‘I am the end of time’ morphs into ‘I am lost’ and the power of Belz’ lyricism is paramount.

Ben Van Lier

Next comes an additional unforeseen surprise in a play that is already chock full of them. Mary Kelly, we discover, is in actually in love with Harvey the hopeful lover and an alternative ‘love that dare not speak its name’, not in Queen Vic’s esteemed company at any rate, rears its rather gorgeous head.

Sickert confronts Gull and we get a Belz classic from the gob of the surgeon. ‘What a piece of work is a woman’ he begins, and what follows is super work from both men. Gull tells Sickert to ‘do something that really matters’ and the men part.

By now the ritualised rhetoric of the Masonic Lodge is punctuating everything as Gull falls deeper into the well of his psychopathy. The Newsboy (Adam Rohe) declaims the bloody details of the Ripper’s deeds and with each pronouncement rips down one of the floor to ceiling portraits. It’s pure Brecht and the pragmatic nature of the classism that permeates this entire narrative is momentarily, but repeatedly, ripped bare. It’s an appallingly painful experience seeing each banner torn to the floor as barely a person in the English-speaking world has not heard, and been affected by, hearing the names of the Ripper’s poor, wretched victims.

We know the end is close when we hear the refrain of ‘London Bridge is falling down’ hanging like mist in the air, discover that Joe, Mary Kelly’s pimp, has been gone for a month and that Kelly ‘has a little Sickert in her belly.’ She knows the baby is his because, despite her profession, Sickert is the only person with whom she has had actual intercourse. ‘I offered’ she says ‘and you drowned yourself in me.’ Sickert is shocked to find Kelly in bed with Harvey and even more so that she is pregnant with his child, his ‘work of art that really matters’.

Ascia Maybury

Sickert and Kelly each recognises that the only thing all the women – except the one murdered as a thrill-kill by Gull whose rampages are evolving – have in common is the knowledge of Eddy Victor’s true identity and that this is a signed death warrant for the one woman remaining with this knowledge, Mary Kelly herself. Sickert pleads with Kelly to leave London for her own safety but Kelly will not leave Harvey. We learn from Gull that even The Masonic Brotherhood think that he has gone too far, that Kelly’s life is virtually over because ‘you can’t hide from the grandmother’ and that ‘she’ll be hunted down.’

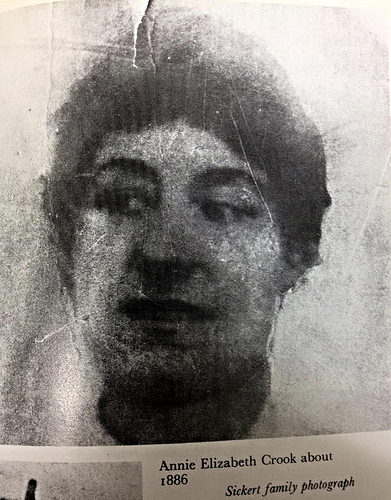

Annie Crook

‘I am the first thought’ Gull chants, ‘I am the light. I am the resurrection’ and the magniloquence finally takes him over. We are stunned by Belz’ definitive horrific exposé as he has Sickert betray Kelly’s whereabouts to the murderous Gull and it seems that her fate is sealed.

Esmee Meyers

The ending of the play I will leave with the Ripper himself, in the deepest shadows. Belz is very clear as to what happens next but I won’t be. There will be other productions of this excellent work and you’ll just have to go and see how it ends for yourself. Or better still buy copy.

‘Yours Truly’ is a deeply satisfying piece of theatre. It’s invisibly directed and the performances are top notch. The production values are good, the technicals impressive, the costumes evocative of both class and time and the text is quite superb but it’s the acting that really carries the day.

As Walter Sickert, Blair Strang hits all his marks. It’s a strong performance of an enigmatic role and Strang connects all the dots for us without becoming a cypher. It’s clever work and it’s good to see him back on the stage.

As the newsboy Adam Rohe does all that is asked of him. He leads us into the theatre before the play begins with a ‘read all about it’ joie de vivre and ticks off each of the murders by tearing down a floor to ceiling portrait with business-like aplomb.

Adam Rohe

As Harvey the hopeful lover, Romy Hooper presents a credible foil for Mary Kelly. It’s an effective performance which balances the play nicely.

As Eddy Victor the prince, himself thought at one time to be the murderer, Ben Van Lier is suitably royal, suitably vacant when required, and suitably in love to convince us of his passion for Annie and his crippling fear of his grandmother.

It is the trio of Annie Crook, Mary Kelly and Sir William Gull however who impress the most. As Annie, Esmee Meyers enables us to love her and to feel for her. Without this affection the play has no real heart. We believe implicitly in the love she feels for her child and for her prince, and her circumstances, as out of her control as they are, cause us considerable grief. Meyers’ performance is selfless and skilful and she serves the play extremely well.

Ascia Maybury is the classic ‘whore with a heart of gold’ but she’s actually much more than that. In Maybury’s skilful hands Kelly is a real person with real feelings and we love her for it. Inhabiting the character of Mary Kelly is an actor of extraordinary capability. She is courageous, takes risks and reaps the rewards with a fine performance.

As the psychopath Sir William Gull, Stephen Brunton speaks the text with intelligence, guts and courage. On a superficial reading, this character might be seen to be somewhat separate from the play. His rhythms are different, he carries the weight of the ritualistic Masonic rhetoric, and he’s ultimately quite, quite mad. He is also extremely credible, seems to be from a different class to everyone else and yet, through his profession, he also has the feel of a man of the streets. In the hands of Stephen Brenton, Gull is painfully real. He’s believable enough for us to see him at the palace looking after the aging queen but he’s equally credible as London’s nightmare, skulking in the Whitechapel streets doing the business of the crown with alacrity and no shortage of intense personal pleasure.

As I said at the start of this review I am a serious fan of Albert Belz’ writing and his exceptional theatre nous. His scripts have the power and the acumen that Greg McGee aspired to but never quite achieved. He defies labels too, which means he can go anywhere at any time and, best of all, he takes his time. I look forward to the next Belz work but I’m happy to wait until he’s ready. ‘Yours Truly’ is a perfect example of Belz knowing when the work is cooked and the number of productions of ‘Yours Truly’ with different casts and produced by different companies bears testimony to this.

I know this is a long review by some standards. If you’ve got to the end I hope you feel that your time wasn’t wasted. I’ve looked for a rule that says reviews should be this many words or that many paragraphs and I can’t find one so until I do I’ll start at the beginning, say what I want to say, mean what I do say, and finish when I’m done.

So there.