‘But he could tear the horns off bulls’.

When discussing the comparative merits of a range of karate disciplines this statement was put forward as advancing Kyokushinkai karatedo to the head of the queue. It seemed rather incongruous and didn’t quite fit with what I had come to understand were the underlying principles of karatedo so I asked who was being spoken about. The answer equally surprised me, ‘Oyama Sensei’.

The role played by Masutatsu Ōyama in the founding of Seido karatedo has been well documented but is worthy of repetition as it impacts on this study which looks at Seido karatedo principles and philosophy and compares them with those of Kyokushinkai, the source from which it grew, and endeavours to point to why there was a parting of the ways.

Ōyama Sensei, along with Kurosaki Sensei whose role is frequently understated in the literature (Jarvis, 2005), founded Kyokushinkai karatedo in 1964.

Kyokushinkai, or ‘the society of the ultimate truth’, had an underlying philosophy of hard training, self development and discipline and, as such, mirrored many of the other budo-based martial arts disciplines that were beginning to gain international attention at that time through such martial arts films as Come Drink With Me (1966), Dragon Inn (1966), One Armed Swordsman (1967) and Chinese Boxer (1969).The key populist figure in this evolution was Bruce Lee.Lee, born in San Francisco, spent his formative years in Hong Kong. He began training in Wing Chun under the legendary Yip Man when he was 13 before returning to America for higher education at the age of 18.

In 1959 he began teaching a form of kung fu and, in 1965, founded his own discipline Jeet Kune Do. Lee, almost single-handedly, popularised the martial arts movie through films such as Fists of Fury (1971), The Chinese Connection (1972) Return of the Dragon (1972), and Enter the Dragon (1973).

Sadly, though anecdotally, these films spawned a generation of hard kicking, hard punching westerners who engaged with the martial arts from an exclusively martial perspective and failed to engage with the underlying philosophies of discipline, self improvement as espoused by Ōyama and the traditional codes of budo, bushido and the world of the samurai.

It has been said, and this essay is based on this understanding, that Kyukushinkai was the karate discipline most at risk of corruption because, in the first instance it was a full contact ‘knockdown’ form ~ otherwise known as Japanese full contact karate ~ and, in the second, Mas Ōyama, in his laudable desire to see Kyokushinkai internationalised – at its peak it had 12 million practitioners – was himself drawn inexorably into the vortex of fame and egocentricity.

Hence, ‘the myth of invincibility’ and the almost instant demise of the Kyokushinkaikan empire, initially in 1976 with the departure of Keiji Kurosaki and Nakamura Sensei who had brought Kyokushinkai to the US, and then again on Ōyama’s death in 1994.

‘Full contact karate’ is a term used to describe a particular form of competitive sparring (kumite) which allows, not only full contact between competitors but includes knockdown and knockout as a means of winning. Other martial arts disciplines limit kumite competition to light or semi-contact sparring where knockout results in instant disqualification. The term is also used to identify schools and disciplines where full contact is allowed and those where it is not.

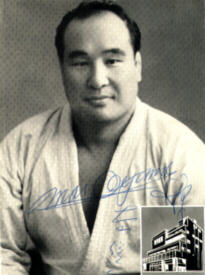

Masutatsu Oyama Sosei

This is important because a dissatisfaction with full contact karate underpins the breakaway from Kyokushinkai by Ōyama‘s chosen successor, Nakamura Sensei.

Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura

The mid 1970’s saw the evolution of a series of world championship events that pitted various martial arts forms such as Muay Thai, Kyokushinkai, Shotokan and Wing Chun against each other with no weight restrictions. The aim of these events was to prove beyond doubt which discipline produced the strongest fighters and was, therefore, the best of the best.

At the same time a parallel movement was evolving that had, at its core, a desire to return to the fundamental beliefs on which the martial arts in general, and karatedo in particular, was based. Cynics might encourage us believe that the growing influence of martial arts in litigation-driven America required teachers and dojo managers to protect themselves by removing full contact sparring as a competitive option to avoid students and practitioners engaging in the court process should they find themselves injured but this was not the case.

From 1964, when Kyokushin was founded, Oyama Sensei undertook a process of evangelising to bring his new form to the world. He achieved this by choosing instructors who were skilled at marketing and opened new dojo in areas where the Kyokushinkai discipline was not practiced. These instructors would then stage Kyokushinkai demonstrations in public places and so gain a following for the new dojo.

This process was quickly established internationally with dojo opening in the Netherlands (Kenji Kurosaki), Australia (Shigeo Kato), the United States in 1966 (Tadashi Nakamura, Shigeru Oyama, Yasuhiko Oyama and Miyuki Miura) and Brazil (Seiji Isobe) and a reverse trend occurred with students from other parts of the world traveling to Japan to train with Oyama Sensei himself (Jarvis, 2006) .

Masutatsu Ōyama Sosei

Many notable students from New Zealand engaged in this intensive process including Renzie Hanham, Trevor Trainer, John Jarvis and Andy Barbour with Hanham and Barber being instrumental, subsequently, in the establishment of Seido Karate in New Zealand while Jarvis went on to head the Okinawa Goju Ryu discipline in this country.

Hanham and Barbour remain active in Seido Karate with Hanham head of the New Zealand branch and Barbour head of the South Island branch. Both have reached 8th dan black belt and hold the title of hanshi.

Jarvis was the only karateka from this exclusive group to retain his kyu grade ranking (1st kyu, brown belt) with the others having to forgo all previous recognition and return to white belts as their training had been from books only .

Jarvis, a New Zealander who trained in London under Steve Arneil who had himself been trained personally by Ōyama, was able to retain his grade (Jarvis, 2006; May, 2010).

From 1969, through the auspices of Kyokushinkai and Ōyama Sensei, a series of All Japan Full Contact Championships took place and in 1975 the First Open Full Contact World Karate Championships were held in Tokyo. This event was, to some extent at least, the beginning of the end of the relationship between Mas Oyama’s Kyokushinkai and Tadashi Nakamura.

This is not to say that Kyokushinkai World Championship events ceased to exist, more that these events, held every four years, became the domain of a number of disparate organisations each purporting to represent Kyokushinkai and each producing their own world champion. These events are often referred to as The Karate Olympics.

The dissatisfaction felt by Nakamura Sensei and reflected in the eventual defection of other key figures, Kurosaki Sensei to Japanese kickboxing, Steve Arneil and John Jarvis to Goju Ryu being the most notable, was contributed to by the Kyokushinkai tradition of 100 man kumite where one fighter would undertake 100 consecutive two minute bouts with a one minute break between bouts.

Jarvis, one of only 17 people to have completed this feat at Kyokushinkai honbu, questions the tradition that Ōyama fought 300 men over a three day period in a 300 man kumite (Jarvis, 2006) but this is representative of the myth of invincibility that surrounds Kyokushinkai and is perhaps best reflected in a photograph reproduced in Jarvis’s book Kurosaki Killed the Cat. The photograph shows the author standing in front of the mural outside the Tokyo headquarters of Kyokushinkai.

The mural shows Ōyama in the process of ripping the horns off a bull.

The controversial mural

Groenwold, in Karate the Japanese Way, says ‘Kyokushin culture believes that accepting a “challenge” represents a Kyokushin practitioner’s commitment to the principles of the art. One way to participate in a challenge, in which a Kyokushin student tests his/her courage and desire to defeat one’s adversary, is through tournament competition.

Groenwold goes on to say ‘The impact of Kyokushin rules upon martial art students has been criticized for a long time, yet there is little indication of possible changes on a worldwide scale, as resorting to protective gear is considered to be against spirit of Kyokushin, and imposing restrictions on contact hardness may result in just a variation of Shotokan competitions. The amount of Kyokushin “spin-off” schools that try to overcome the situation is still growing.’

And therein lay the problem for Nakamura Sensei and the others.

Tadashi Nakamura, the favourite student of Ōyama Sosai, was the youngest to achieve a black belt (shodan) in Kyokushinkai. He began his training in 1953 and in 1961 he won the All-Japan Student Open Karate Championship for the first time.

Having instructed members of the US military at the Camp Zama base near Tokyo and, in 1962, beaten the Thai kickboxing champion in a competition to determine which country had the superior martial art, Nakamura became something of a national hero, a status that lead to his becoming chief instructor at the Kyokushinkai honbu and achieving his 7th dan black belt.

In 1966 Nakamura was chosen by Oyama Sosei to be his representative in the US and to open a dojo in New York which he did in a studio space at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Nakamura, reflecting on this time writes ‘I immersed myself in instructing at the dojo, thinking all the time that whatever happened I would bear it and pull through until I succeeded. It was necessary to have the sort of determination and responsibility that ensured that my own will persevered until I overcame all obstacles’ and in 1971 the Kyokushinkai honbu was established in New York.

The growth of Kyokushinkai in the US was astronomical and it became impossible for Nakamura, then Chairman of the US branch, to ensure that the standard of instruction remained high throughout all the new dojo. He became increasingly concerned that Ōyama’s focus was primarily on the growth and popularity of the discipline he had founded rather than on ensuring that standards of training and instruction remained high throughout the country.

This, and his concern that the underlying budo principles were being overlooked, caused him to ‘respectfully withdraw’ from Kyokushinkai in 1976 following The First World Open Karate Tournament held in Japan, a tournament that he felt was ‘rigged’ in favour of the Japanese entries. The tournament is recorded in a documentary film entitled ‘Fighting Black Kings’ and the opening frames are voiced as follows:

‘Every man, deep in his subconscious mind, desires to become a star. Karate is a world apart, a world of men. Day and night in New York, Paris, London, and throughout the world, young men have undergone strenuous training in a bid to challenge the karate champions. This documentary film shows the world and the men of karate. The expert fighters who will participate in the first World Open Karate Tournament held in Japan.

Within this voiceover of the film lies a second dissatisfaction Nakamura felt with Kyokushinkai and karate as it was developing in the west, primarily as a sport for the strongest of men only. He felt that the principles of budo were being swamped in a race to be biggest, toughest, and strongest and, as a direct response to this, Seido Karate was founded in 1976 on the principles of love, respect and obedience to the moral laws of the universe.

The Kyokushinkai emblem and Masutatsu Oyama Sensei

What followed is best assessed by Christopher Caile on www.fightingarts.com: ‘Though Nakamura was prepared for the difficult task of building his own organization in the United States, he hardly expected the vehement response from Japan. Oyama moved to banish him from the martial arts world. He was defamed, vilified and, finally, on a cold night in February 1977, gunned down in a Manhattan parking lot.

But Nakamura recovered and persevered. He founded Seido Karate and has built it into an organization with more than 50 affiliated dojos around the world. Its New York Honbu is one of the largest schools in the world. Most important, Seido represents the ideals for which Kaicho Nakamura had fought and sacrificed. Since the founding of Seido Juku, Nakamaura has crystallized his ideals and beliefs into a philosophy of living that has given strength and inspiration to thousands of students around the world. His innovative teaching methods offer a step by step program to strengthen the mind, body, and spirit – a unique approach that makes Karate available to men and women of all ages and abilities.

In addition to returning karate-do to its roots by ensuring that Seido Karate was accessible to women and children and families of all ages who wished to train together, Nakamura added community service to the list of essential functions of his worldwide organisation and established classes at the New York honbu for physically, socially and intellectually disabled students who wished to train. This attitude has spread worldwide and classes regularly contain mainstreamed students of this nature and, where numbers warrant it, specific classes for, for example, the visually impaired.

As Nakamura states on his website: ‘Martial arts are more popular now than ever before in history. Because of movies, television and magazines, karate is widely perceived as a purely physical fighting art. Seido chooses to follow a different path, one that directly – and effectively – connects its students to the origins of karate and the bushido spirit of the samurai.

Nakamura goes on to say ‘My purpose in founding Seido Karate was to show what I feel is the true essence, the kernel of true karate-do: the training of body, mind, and spirit together in order to realize the fullness of human potential’.

The website continues: Seido seeks to develop in each student a ‘non-quitting’ spirit. No matter what the obstacle or difficulty – emotional, physical, financial – we want students to feel that, though they may be set back, they will never be overcome by any of these problems. The sincere practice of karate can impress this idea into the spirit. This is the modern interpretation of the bushido spirit of the samurai.

The lineage of Seido Karate includes karate-ka who changed the face of the martial arts over centuries. These karate-ka ~ Bushi Sokon, Anko Itesu, Master Gichin Funakoshi, Keiji Kurosaki, Chigun Miyagi, Akio Fujihara, Steve Arneil, John Jarvis and Ōyama himself ~ in the main, adhered to the principles of the Samurai and those laid down by Miyamoto Musashi, namely:

• Gi: making the right decision, decisions taken with equanimity, the right attitude, and exemplifying the truth. When we must die, we must die. This is the spirit of rectitude.

• Yu: exhibiting bravery tinged with heroism at all times;

• Jin: expressing universal love, benevolence toward mankind; and compassion;

• Rei: choosing the right action ~ an essential quality, acting always with courtesy;

• Makoto: acting always with utter sincerity; truthfulness;

• Melyo: living a life of honour and glory;

• Chugo: always showing devotion, loyalty.

Woodblock print of Miyamoto Musashi (partial)

As with any mythology ~ and the legends and anecdotes that surround Matsutatsu Ōyama must, to some extent, be seen in this light ~ there is always a modifying view.

In this case these views are expressed by two highly regarded New Zealand karate-ka, one of whom ~ Kyoshi Dennis May 8th dan black belt Okinawa Goju Ryu, was Mas Ōyama’s live in student (Uchi-Deshi) and lived in the Tokyo honbu while studying Kyokushinkai Karate, Kendo and Judo full time ~ and the other, Sempai Fiona Fulton 3rd dan black belt Seido Karate, kata instructor at the Morningside dojo in Auckland.

May stated recently that Ōyama was a most generous instructor and friend, hard-working, disciplined and kind, whose attempts to bring what he loved most to the largest number of people but that this approach created a mythology that, while having a kernel of truth, was mostly incorrect. He went on to suggest that Ōyama struggled with a form of racism and, being Korean, was never fully accepted in Japan which may have lead to his need to ‘overstate his case’.

Fulton perhaps summed up the man and his approach to life and karate-do by saying simply that ‘he loved his students and he loved his country’.

So the debate rages on, though most in Seido Karate freely acknowledge the genius of their teacher’s teacher and his fine and deserved place in the lineage of great karate-ka while acknowledging that, at worst, he was more than likely the author of his own downfall.

References

(2010). “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce_Lee.” Retrieved 03 June, 2010.

(2010). “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knockdown_karate.” Retrieved 03 June, 2010.

(2010). “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kyokushin_kaikan.” Retrieved 03 june, 2010.

(2010). “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martial_arts_film.” Retrieved 03 June, 2010.

Caile, C. “http://fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=109.” Retrieved 19 may, 2010.

Caile, C. (2010). “http://fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=109.” Retrieved 03 June, 2

Caile, C. (2010). “http://www.fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=136.” Retrieved 03 June 2010.

Fulton, F. (2010). Matsutatsu Oyama. L. Matheson. Auckland, New Zealand, Facebook: one.

Goto, S. (1976). Fighting Black Kings. Fighting Black Kings. Japan.

Groenwold, A. M., Ed. (2002). Karate the Japanese Way : . Karate the Japanese Way Toronto, Canada, Trafford Publishing.

Jarvis, J., Ed. (2006). Kurosaki Killed the Cat Wellington, New Zealand, Rembuden Publishing, Upper Hutt.

May, D. (2010). “http://www.karatenz.com/index2679.html?page=2.” Retrieved 03 June, 2010.

May, D. (2010). Matsutatsu Oyama. L. Matheson. Auckland, New Zealand, Conversation: 1.

Nakamura, T. (2010). “http://www.seido.com/about-seido/seido-philosophy.” Retrieved 20 May 2010, 2010.

Nakamura, T., Ed. (2001 ). The Human Face of Karate: My Life, My Karate-Do. New York, Shufunotomo, Co., Ltd.

T. Deshimaru; N. Amphoux, Ed. (2006). The Zen Way to Martial Arts: A Japanese Master Reveals the Secrets of the Samurai.Compass; (Paperback).